Restoring communities after an industrial accident is one of the areas of great potential for public interest litigation. The Bhopal Gas tragedy is one such incident, though results have been mixed and slow to materialize, if at all.

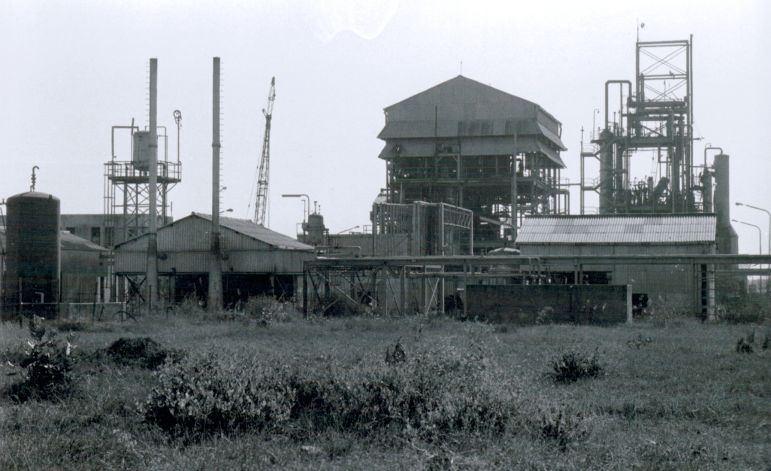

The Bhopal Gas tragedy occurred around midnight on December 2-3, 1984. It was a chemical accident at the Union Carbide India Limited (UCIL) pesticide plant in Bhopal, Madya Pradesh, India where over 500,000 people were exposed to methyl isocyanate. Over three thousand people died instantly, and hundreds of thousands continue to deal with long term impacts to their health, such as cancer, miscarriage, and heart disease. (The Guardian, 2019) To compound the issue, during the investigation, the site could not be cleaned up and remained toxic for decades, continually exposing the surrounding communities while the corporations at fault continue to pass the blame and avoid accountability. (Bhopal.com).

Two companies in particular were at risk of incurring liability for the tragedy. The first is UCIL, the Indian company that managed and operated the plant at the time of the leak. The company was majority owned by Union Carbide Corporation (UCC), an American Chemical company, with Indian banks and the Indian public holding a 49.1% stake. In 1994 the UCC sold its stake in UCIL to Eveready Industries India Limited (EIIL), and ended clean-up on the site in 1998 when it terminated its lease and turned control over to the state government. In 2001 Dow Chemical Company purchased UCC. This complicated and changing corporate structure has made the resulting claims even more difficult to persue.

Civil and criminal litigation was pursued in both the United States and India against the companies and some corporate heads of UCC and employees of UCIL. On December 4, 1984, Warren M. Anderson (Chairman and CEO of UCC) arrived in India to assist with the disaster and was immediately placed under house arrest, brought to the Delhi airport and urged to leave the country, which he does on December 10. Within days of the disaster, American personal injury lawyers brought civil litigation claims in the U.S. against UCC on behalf of individual claimants. The cases were consolidated before District Judge John F. Keenan in New York. (Bhopal.com). In March of 1985 the Indian Government passed the Bhopal Gas Leak Disaster (Processing of Claims) Act, 1985, which confers “certain powers on the Central Government to secure that claims arising out of, or connected with, the Bhopal gas leak disaster are dealt with speedily, effectively, equitably and to the best advantage of the claimants and for matters incidental thereto.” In December, UCC executives testified before two subcommittees of the US House & Energy Committee regarding the disaster. (Bhopal.com Archive).

UCC moved to dismiss the case on forum non conveniens, arguing that Indian courts were better positioned to hear the case. In May 1986 Judge Kennan granted the motion on the condition that UCC accept the civil jurisdiction of the Indian courts.

In India, numerous routes of litigation were undertaken: civil litigation, criminal litigation, curative petition litigation and public interest litigation.

The first case was a civil suit brought by the Indian government in September 1986 in the District Court of Bhopal, and UCC appeared as required by the US suit dismissal conditions, along with UCIL. After almost 3 years of litigation and 24 days of hearings, a global settlement of $470 Million was agreed, and paid, in February 1989. However, when the opposition party took power in India in November 1989, it reopened the issue of if the compensation was adequate, and ordered the Supreme Court to reconsider. The decision and the Government’s power to stand in for the victims was upheld in October 1991 in addition to further obligations being imposed on the Indian government and UCC to treat victims. In the decades that followed, activists have repeatedly pushed the government and courts to reevaluate the decision on the grounds that the victim count was under estimated and the amount offered inadequate, to no avail.

Criminal proceedings on the matter were not far behind, and were first initiated in December 1987 when the Indian Central Bureau of Investigation announced they were investigating corporate entities–including UCC and UCIL–UCIL managers and UCC chairman Warren M. Anderson with various charges including “culpable homicide not amounting to murder”. The charges were dropped with the 1989 settlement, but opened up again by the 1991 judgement from the Supreme Court. Over the following years the Indian Government requested Anderson’s extradition, which the US refused, and the UCIL managers were convicted of Negligence in 2010. Today, their appeals of the verdict continue to run through the appeals process.

After the 2010 criminal convictions, the Indian Government subsequently filed a curative petition with the Indian Supreme Court, requesting additional funds, relief, and rehabilitation in excess of $1 Billion from UCC. Some public interest groups pushed to request eight times that amount. The Indian Supreme Court was unmoved, and dismissed the petition in March 2023.

Finally, various litigation that is purely focused on adjacent public interest issues have also been filed. Site remedial and waste disposal have been a contentious issue, and in Union of India (UOI) v Alok Pratap Singh & Ors, the State of Gujarat challenged Madhya Pradesh High Court orders to incinerate the waste, seeking to stay the order in lieu of seeking another, safer method of disposal. This was granted in 2012 and has not yet been revisited. In 1996, Research Foundation for Science vs. UOI was filed in the Indian Supreme Court, arguing that industrial waste sites violate a constitutional right to life. The Supreme Court has since implemented various related orders, noting in 1997 that industrial sites should not be approved “without ensuring the availability of the required safe disposal sites”. Industrial waste reports have been ordered (and sometimes ignored) to assess groundwater and soil contamination, but clean-up efforts have been minimal and slow to materialize.

Once again in the US after the turn of the century, efforts have been similarly frustrated. Three class action suits were filed in the US district court for the Southern District of New York against UCC and Warren M. Anderson. First, the Bano case in 1999 sought to avoid the preclusive effect of the Settlement reached in India, arguing that respondents had violated international law and had failed to appear for criminal proceedings in India. Plaintiffs later amended the Bano complaint to add environmental pollution claims unrelated to the leak and alleging property damage in nearby colonies as a result of groundwater contamination resulting from the plants operation. In 2006, the US Court of Appeals affirmed Judge Keenans ruling, affirming that plaintiffs lacked standing due to the Bhopal Act granting the Indian Government exclusive representation of the victims, plaintiffs were barred by the settlement the India government obtained, that the 1986 dismissal only covered civil, and not criminal proceedings in India, and dismissing the injury claims and remediation order. (Bano Decision).

The second class action suit filed in November 2004 in the US was the Janki Bai Sahu (Sahu I) case, brought by 13 people on behalf of themselves, their family, and others similarly situated. The Court of Appeals affirmed Judge Keenan’s ruling in June 2013, rejecting plaintiff’s claims for UCC’s liability for participation in the creation of pollution and alleged environmental contamination, designing a faulty waste disposal system at the plant, dismissing related claims of fault and asserting no individual liability for Mr. Anderson, and rejecting theories of direct and indirect liability. (Sahu I). The final class action case was Jagarnath Sahu et al v. UCC and Warren Anderson (Sahu II case), filed in March 2007 after the dismissal of the Bano case. Plaintiffs alleged property damage. The case was stayed pending the final appeal in Sahu I, and in 2014 Judge Keenan dismissed Sahu II, stating the company could not be sued for ongoing contamination.

SOME HARD LESSONS

As the litigations and investigations continue, I would like to consider what greater considerations the case can offer to lawyers interested in using public interest litigation as a tool for climate cooperation.

Multinational corporations are hard to call to account and governments have not yet caught up

UCC and UCIL are separate entities, but connected. The fact that UCIL exists serves to shield UCC from some of the financial and criminal consequences of its acts (but reaps the benefits as an owner), and its international status makes it difficult to properly suss out jurisdiction, and bring the parties to court for trial. The US refused to extradite Anderson for a criminal case, citing the need for India to prove “prima facie” or on the face, that a criminal case exists. Anderson died and was never brought to India to face charges, while the managers at UCIL were eventually convicted of negligence. But in America, because Anderson’s lawyers successfully argued that claimants lacked standing because the Indian government had passed the Bhopal Act, and then later cleared Anderson of liability. Anderson’s status as head of UCC and an American shielded him from the consequences of his actions purely by virtue of the location of the tragedy. And as far as the civil proceedings are concerned, the earlier US civil cases were used as leverage to gain UCC’s cooperation in the Indian civil case, which would not have happened otherwise. Governments have not yet developed effective mechanisms to force accountability on uncooperative multinational corporations and their officers where a criminal act occurs in a foreign jurisdiction.

Who is in power matters

Especially in the case of the Indian Government, politics has power over what is in the public interest. While in 1989 a $470 Million settlement was deemed sufficient, that was not the case under the opposition a mere six months later, who sought to vacate the settlement and seek a larger compensation package. Had the decision to bring the case to court, or even to settle occurred just a few months later, there may have been a more substantial payout for the victims, and perhaps more public will to investigate the true scope of the injury to people and place.

Sometimes early gains can lead to large long term losses

While some early gains were had in the litigation from the 1990s, especially considering the use of the US civil cases to bring UCC to court in India and the $470 Million settlement, many of those gains made other wins further down the road harder to achieve. That settlement was premature because the true scope of the damage was not known. While some of the issues arose out of the difficultly of establishing an interim relief fund for victims, which made it necessary to come to a settlement as quickly as possible, the settlement itself has not been sufficient to compensate the victims or care for their health over the long term, and there remains the issue of clean-up. Similarly, the earlier decision to dismiss the case in the US made holding Anderson accountable in the US system once extradition became impossible much more difficult.

What is thought of as “Public Interest” is in fact a complicated web of public and private, civil and criminal

Just because there may be specific instances of what can be considered public interest litigation, does not mean that the accompanying public, private, civil, and especially criminal suits aren’t part and parcel of what public interest litigation can achieve. Matters of the public interest are inherently personal…to someone. Individuals have their lives derailed and their communities destroyed, and public interest litigation is a method to address the issues of the larger community in light of the experiences of individuals. These suits can send signals to other corporate actors that their actions can have real, criminal consequences, and give a name for the larger public to attach the story to, and empathize with.

The Bhopal tragedy is still unfolding today, but contained within its tangled and decades long history are lessons the new wave of public litigation lawyers should consider as the building blocks to build new, successful approaches to litigation.